How Does Pectin Work? How to Make Jam Set.

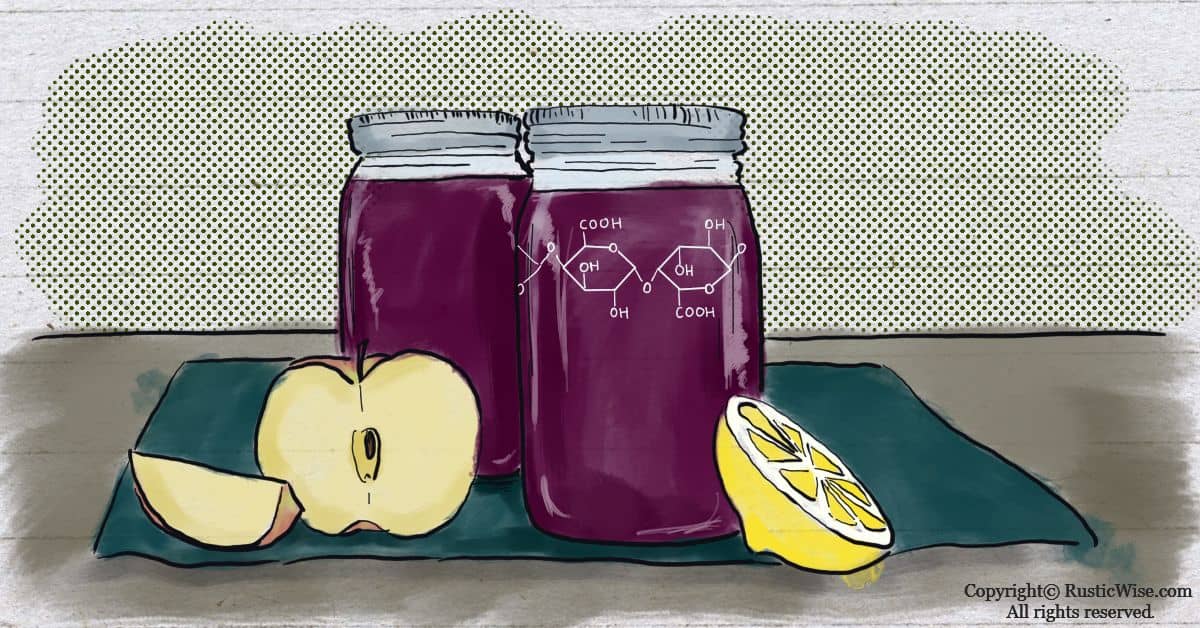

How does pectin work? Pectin is the backbone of any good jam or jelly: it’s a naturally occurring carbohydrate found in the cell walls of plants. It helps to create a gel-like consistency by creating a network or web of bonds with other pectin molecules when conditions are just right. To make a successful jam, you need to activate pectin through heat, and have the right amount of sugar and acidity as well.

If you’re looking to make some tasty homemade jam, understanding how pectin works will help you make a better quality jam (which is something we could all get behind!).

We’ll discuss how pectin works, how to use it for canning jelly and jam, different kinds of commercial pectin including HM (high methoxyl) and LM (low methoxyl), plus troubleshooting common jam issues.

What exactly is pectin?

Pectin is a natural plant substance that helps make jams and jellies set. It’s a polysaccharide, a water-soluble type of thread-like carbohydrate or fiber found in most fruits and vegetables.

Pectin helps turns fruit juice into a gel and helps it set without too much sugar needed.

Pectin occurs naturally in fresh fruits, especially apples and citrus fruit. As the fruit ripens, the amount of pectin present in the fruit walls decreases; this is why underripe, or just-ripe fruits contain more pectin than overripe fruits.

It’s important to note that different types of fruits contain different amounts of pectin (1). For instance, apples have a higher amount of pectin than strawberries or raspberries.

Fruits with high pectin content:

- Apples of all kinds including crab apples and sour apples

- Lemons (particularly citrus peels)

- Currants

- Cranberries

- Loganberries

- Sour plums

- Green gooseberries

- Quince

Fruits with medium pectin content:

- Ripe apples

- Blackberries

- Grapefruit

- Grapes

- Oranges

- Sour cherries

Fruits with low pectin content:

- Apricots

- Peaches

- Pears

- Raspberries

- Strawberries

Why do you need to add pectin to jam when there’s already natural pectin in fruits?

As you can see, some lower pectin fruits need a boost of pectin to properly set. This is especially true in many favorite jamming fruits like raspberries and strawberries.

Commercial pectin is commonly made from apple and citrus peels with dextrose to bind ingredients together. It’s safe to use and doesn’t change the flavor.

The decision to use a store-bought pectin, or make your own pectin is a personal preference.

A commercial pectin may help speed up the cooking process, and perhaps cut back on the sugar a bit.

If you’re choosing to go the au naturel route, know that the cook time is a lot longer (which affects the nutrients present in the fruits), and you’ll be adding a lot more sugar.

But good jams and jellies are made either way.

You can find pectin in larger grocery stores near the canning supplies or with other baking ingredients. You can also buy it online.

How does pectin work when making jam?

There’s a bit of science going on when we’re making homemade jam. Knowing the ins-and-outs of how pectin works will help you make a better jam.

At its essence, here’s the basic formula for jam:

Jam = fruit + pectin (+ heat) + acid + sugar

Let’s take a look at the different ingredients and how they interact.

Fruit

When we chop up and heat fruit, we’re helping to break down and release the naturally occurring pectin found in its cell walls.

The type of fruit we choose to use has a huge impact not only on the flavor of the jam, but also the amount of pectin required to turn that fruit into jam or jelly.

Fruits that naturally contain plenty of pectin such as apples can be made into jelly without the use of added pectin. Others with low pectin such as strawberries and raspberries need a bit of help in the pectin department.

Sometimes you can add high pectin fruits to low pectin fruits to increase the pectin factor. We mentioned earlier that the ripeness of fruits also affects pectin content: riper fruits contain less pectin.

Tip: According to the National Center for Home Food Preservation (NCHFP), one-quarter of the fruits used should be underripe in your jelly recipe when forgoing added pectin.

Pectin + acid

Pectin is the natural thickening agent in fruit. When we cook a jam, it’s our goal to have some of that pectin work on the watery sugar mixture and thicken up into a spreadable, not too-thick, not too-thin consistency—the quality of a good jam.

But to begin with, pectin on its own doesn’t work. It needs the application of heat to activate.

Pectin molecules have a negative charge which makes them repel one another and stick to water. Water is introduced when we prepare fruits (chopping, cutting, and cooking). Naturally-occurring acid from fruits are also introduced during the cooking process.

Acid helps to neutralize the negative ions of pectin so they can repel each other less and stick with water.

Many jam and jelly recipes call for the use of lemon peels or citric acid which helps level up the acidity of the mixture.

Tip: According to the University of Nebraska Lincoln, the “optimum” gel pH is between 3.1 to 3.3. A pH higher than 3.5 won’t form a proper gel, while a pH below 3.0 makes a hard gel prone to weeping. If you remember the pH scale, anything below 7 is acidic.

Sugar

Once sugar is added, the water molecules become attracted to the sugar which allows the pectin chains to get cozier with one another and form a web or network that when cooled, becomes jelly. Sugar works by drawing water away from pectin and forming water-sugar bonds.

The right amount of pectin-threads must get close enough to form a cross-bond to make gel. When this happens, you have jam success!

As you can see, you need the right amount of pectin, sugar and acid to make a good jam.

Note: Your jam mixture needs to reach gel point: 220 degrees Fahrenheit (104 degrees Celsius).

Not all pectin is the same: a closer look at different types of pectin

There are two main types of pectin: HM (high methoxyl) and LM (low methoxyl). Most pectin you’ll find on store shelves are of the HM variety, and this is what you’ll be using if you’re making regular jam with sugar.

For recipes that call for “low sugar” or “no sugar” you’ll need LM pectin. With each packet of LM pectin you’ll find a calcium additive that’s required to kickstart the gelling process. As sugar and acid aren’t used as binders, LM pectin relies on the use of calcium to form bonds. Recipes that are low or no sugar require longer processing times.

Pectin can also come in liquid or powdered form.

Note: Liquid and powdered pectin are not the same thing and can’t be used interchangeably. It’s important to buy the right type of pectin for your recipe. This is because liquid and powdered pectin are added to recipes at different times; using the wrong form of pectin will ruin your jam recipe.

Is pectin the same as gelatin?

While both pectin and gelatin act as a thickener or stabilizer, they are not the same thing. Pectin comes from plants while gelatin is from animals. So pectin is vegan-friendly.

Remember that only pectin is suitable for canning purposes (that is preserving foods for storage at room temperature).

You’ll see many recipes that call for clear gel, or Jello—these are not suitable for canning jelly and jams. Recipes that use these ingredients need to be refrigerated or frozen and aren’t examples of “true” canning. Failure to properly refrigerate or freeze recipes using clear gel may cause foodborne illnesses.

How does pectin work? Troubleshooting common jam issues

When making homemade jam or jelly, it’s so important to first pick a reliable recipe, and then follow that recipe carefully! While it’s tempting to freestyle it or get creative with the amount of sugar you add, you can end up with a jam disaster.

Pectin is sensitive to sugar content and how much liquid is present when it’s added to the fruit mixture. Too little pectin results in a runny batch of jams. Too much pectin may produce jam that’s too stiff.

Because jellies thicken quickly, you have to measure your ingredients carefully the first time to get the right texture and consistency.

Jam that’s too stiff

There are a number of factors that may have contributed to a jam that’s too stiff:

- Too much pectin

- Cooked too long

- Cooked at temperatures that are too high

- Not enough fruits or fruit juices

- Not enough sugar

- Too much underripe fruits (which contain more pectin)

Unfortunately, with stiff jams, you can’t reheat the mixture again to “right the wrongs.” Wait—before you decide to toss that stiff jam, there are many ways to repurpose it. Instead of thinking of it as “jam” use it as a fruity glaze on meat, or heat it up before serving as a syrup for pancakes or desserts.

Or, you can try thinning the jam by adding a bit of water or fruit juice and reheating. Your jam may or not reset and gel properly—store your remade jars in the fridge.

Jam that’s too runny

Jam that’s too liquid-y may have resulted from a number of factors including:

- Not enough pectin

- Not enough sugar (for HM pectin)

- Low acidity (either from the fruit content, or not enough citric acid)

- Using the wrong type of pectin

- Not cooking properly (either overcooking which breaks down pectin, or undercooking which doesn’t allow pectin to set)

Luckily with runny jam, you can try to reheat the batch and adjust your recipe with more pectin as needed.

Related Questions

The shelf life of store-bought pectin

Store-bought pectin has a shelf life—old pectin may not gel as nicely. It’s best to use up commercial pectin by the best-by date for best results.

Is pectin bad for you?

Pectin is a natural indigestible substance found in fruits and vegetables, mainly in the cores and peels. Many commercial (think gummy bears and store-bought jams) and homemade foods (jams and jellies) use pectin as a thickener and stabilizer.

Commercial pectin is extracted from citrus peels and apples. They often contain dextrose as a binding agent. In the U.S., the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies pectin as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) which means it can be used freely in foods. It has the uppermost level of approval meaning the FDA has no concerns over its addition to food or beverages.

👉 If you like this post, see our Ultimate Guide on How To Can Food. 🍎

Would you like more timeless tips via email?

Fun tips to help you live an independent, self-sustaining lifestyle. Opt-out at any time.

References:

- Emery, Carla (2012). The Encyclopedia of Country Living, 40th Anniversary Edition. Sasquatch Books. ISBN-13: 978-1-57061-840-6.

- National Center for Home Food Preservation (NCHFP), General Information on Jams, Jellies, and Marmalades, https://nchfp.uga.edu/how/can_07/prep_jam_jelly.html. Accessed May 2021.

- University of Nebraska Lincoln, Fruit Jellies: Food Processing for Entrepreneurs Series, https://nchfp.uga.edu/how/can_07/prep_jam_jelly.html. Accessed May 2021.

- University of Penn State Extension, Pectin’s Role in Making Jam and Jelly, https://extension.psu.edu/pectins-role-in-making-jam-and-jelly. Accessed May 2021.

- National Center for Home Food Preservation (NCHFP),Stiff Jams or Jellies, https://nchfp.uga.edu/how/can_07/stiff_jelly.html. Accessed May 2021.

- National Center for Home Food Preservation (NCHFP), Remaking Soft Jellies, https://nchfp.uga.edu/how/can_07/remake_soft_jelly.html. Accessed May 2021.

- International Pectin Producers Association, The Safety, Regulation and Labelling of Pectin, https://ippa.info/. Accessed May 2021.

Author: Josh Tesolin

Josh is co-founder of RusticWise. When he’s not tinkering in the garden, or fixing something around the house, you can find him working on a vast array of random side projects.