Natural Lye for Soap Making: How Is Lye Made + Is It Bad for You?

RusticWise is supported by its readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Thank You!

You can make natural lye for soap making by combining hardwood ashes and water in a wooden barrel. This produces potassium hydroxide (KOH) lye which makes soft or liquid soaps. If you want to make a hard bar of soap, you’ll need to use sodium hydroxide (NaOH) which is commercially produced.

The use of lye in homemade soap is widely misunderstood. While sodium hydroxide lye is industrially manufactured, it’s a must-have ingredient when making natural soap from scratch.

You may have heard about the dangers of using lye—it can burn skin, irritate eyes, and is not something you want to inhale. However, when used safely and correctly in the soap making process, lye kick starts the saponification process and is neutralized in the finished soap.

Clear as mud?

If the use of lye in handmade soap turns you off, or concerns you, read on as I’ll try to clear the cobwebs. We’ll look at how lye is made commercially, how you can make natural lye, and how you can still make natural soap using lye. And if you want to make soap without handling lye, it’s called the melt and pour process, which we’ll cover, too.

What exactly is lye?

There are two compounds called “lye” which are sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and potassium hydroxide (KOH). In soap making, we mostly work with sodium hydroxide lye to make those lovely hard bars of cold process or hot process soap.

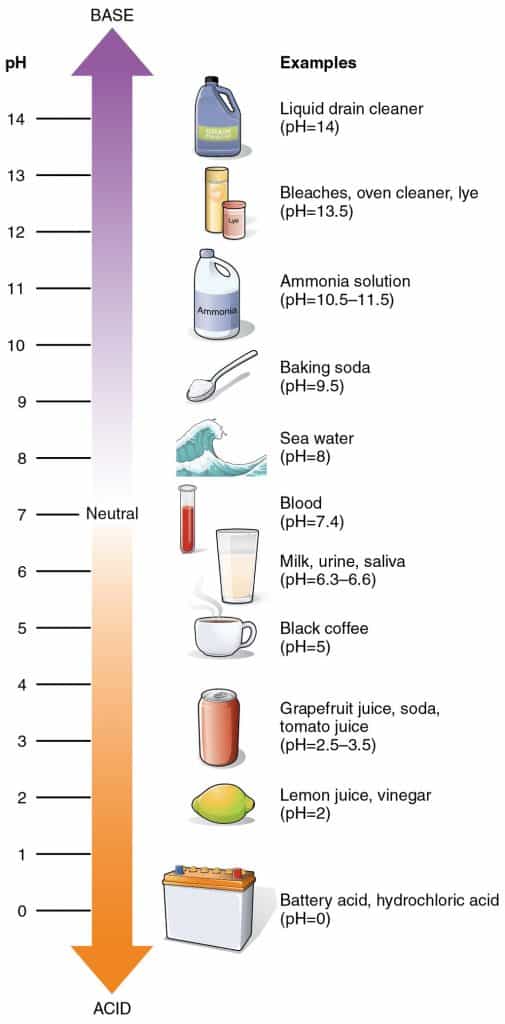

Lye is a strong caustic alkali, or base. (Many people assume it’s an acid because of the way it can eat through clothing, but the opposite is true). Other names that refer to this substance are caustic soda, or soda lye.

Credit: Wikimedia.org

Sodium hydroxide is a very useful compound that can make a variety of household items. Examples include paper, aluminum, drain and oven cleaners, petroleum products, plus soaps and detergents.¹

Food-grade lye is also used to preserve and process foods. Chances are, you’ve probably enjoyed store-bought pretzels, olives, or canned tomatoes. Manufacturers use food-safe lye to add a golden touch to foods (pretzels and other baked goods), preserve, or remove skins.¹

What does lye look like?

At room temperature, sodium hydroxide is a white, odorless substance that comes in a variety of forms: beads, crystals, flakes, pellets, powder, and sometimes a 50 percent liquid solution.

For soap making, we use beads, crystals, flakes, or pellets. This makes it easier to measure.

Tip: Ensure your bottle of lye is labelled as 100 percent pure lye and has no additional chemicals added. Check out places to buy sodium hydroxide for soap making.

Credit: 123RF.com

A quick look at commercial lye production

Every year, millions of tons of sodium hydroxide lye are produced. In 2019, the U.S. produced 11.63 million metric tons of lye.²

The chloralkali process is used to produce lye. This involves electrolysis of sodium chloride (salt, or NaCl) solution to produce sodium hydroxide, lye, and hydrogen.

The BBC has a nice explanation: “Electrolysis is the process by which ionic substances are decomposed (broken down) into simpler substances when an electric current is passed through them.” ³

So when you take sodium chloride (which is essentially salt), mix it with water, and use electrolysis, you get this:

2Na+ + 2H2O + 2e− → H2 + 2NaOH

Now, the next step is important—they need to prevent sodium hydroxide (NaOH) from reacting with the chlorine (Cl).

There are several ways to prevent this from happening. The main and most common way to separate sodium hydroxide and chlorine is through the membrane cell process. (This process uses much less electricity and steam than other methods which makes it the most economical.)⁴

The membrane cell process involves using a porous membrane to isolate the cathode from anode reactions. In this way, just sodium ions and small amounts of water go through the membrane, which makes for a purer form of sodium hydroxide.

The takeaway: Without getting bogged down by the science, commercial lye is produced by mixing salt and water which then undergoes electrolysis to produce two separate products: sodium hydroxide lye and chlorine.

DIY natural lye for soap making

If you’re wondering whether there’s a natural lye for soap making that’s made using elements found in nature, yes, there is. This is an ancient tried-and-tested method which produces potassium hydroxide (KOH), which is also sometimes called caustic potash.

You can make your own natural potassium hydroxide lye by collecting hardwood ashes, preferably from walnut, oak, or fruit wood. (Evergreen trees produce softwood ashes which don’t contain enough potassium needed to produce a strong lye.)

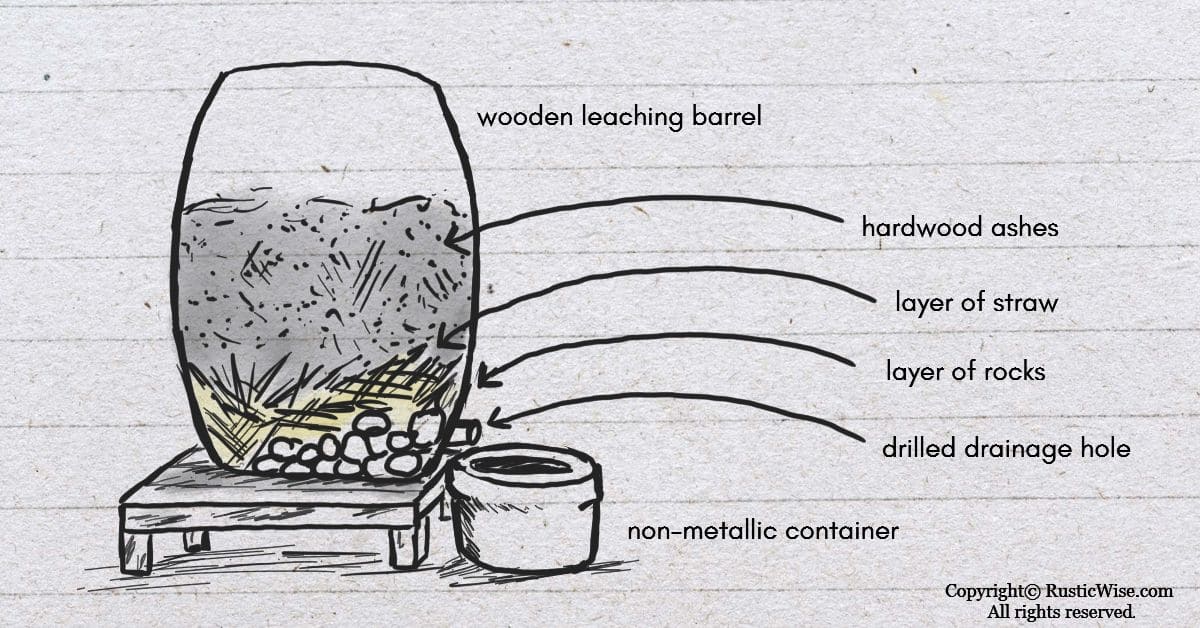

Once you’ve collected a fair amount of hardwood ashes, you’ll need to gather a few supplies, namely a wooden barrel which you’ll use as a leaching barrel, straw and rocks, and soft water or rain water.

You can read the full tutorial on making soap lye the old-fashioned way here.

In a nutshell, you’ll be layering rocks, then straw, and finally the hardwood ashes on top inside the barrel. You will need to drill a small hole near the bottom of the barrel to allow water to leech out.

Next, you’ll add just enough water to create a hardwood ash slurry. You’ll place a cork in the hole and allow the mixture to percolate for several days.

After about a week, you can test your natural lye solution for concentration. There are several ways to do this, but one of the easiest is to do the “sinker or floater” test with an egg. If an egg floats when placed onto the liquid, the lye solution is ready. If it sinks, you’ll need to let it sit for a while longer.

Finally, if your lye is ready, you can use a non-metallic container (ceramic, glass, wood, or high-density polyethylene (HDPE) plastic) to collect it.

To turn your lye into crystals, simply place your container in the sun until the water evaporates. Store your new lye crystals in an airtight container.

Keep in mind that your DIY lye mixture is potassium hydroxide, or potash lye. Potassium hydroxide lye produces softer soaps than sodium hydroxide.

Safety tip: Whenever you’re working with lye (commercial, or homemade), please wear protective gear to stay safe (gloves, goggles, and long sleeves).

What are the ingredients in homemade lye soap?

So now that you have an overview of how lye is made industrially and naturally, you might wonder what ingredients you need to make your own bars of soap.

The most basic soap bars use just three ingredients: lye + distilled water + fats.

The fats or oils you use in your soap affect the finished product. Back in the day, the fats used in traditional soap were lard or tallow that were rendered at home. Using just these three basic ingredients made for a gentle soap.

Nowadays, many people prefer to use a blend of vegetable oil such as avocado oil, castor oil, coconut oil, olive oil, or palm oil. Body butters such as shea butter or cocoa butter add rich moisturizing properties.

And of course, many soap makers choose to customize their homemade soap recipes with their favorite essential oils or fragrance oils, along with colorants and botanicals.

Properties of lye

If you’re new to soap making, it’s helpful to read up about lye safety. Here are a few important things to keep in mind about lye properties:

- When added to water, it creates a strong exothermic reaction. Your lye water solution can reach temperatures of 200 degrees Fahrenheit (93 degrees Celsius)—be careful!

- Wear protective safety equipment such as gloves, safety goggles, and protect your skin when handling lye.

- Store lye in a sealed airtight container as it absorbs moisture from the air.

- Lye reacts strongly with metals like aluminum and magnesium. Stick with stainless steel pots and non-reactive utensils.

- Always add lye to water and NOT the other way around!

Saponification: how lye works in soap making

Saponification is just a scientific term for transforming fats/oils and lye water into soap.

When you have a chemical reaction between a strong base + an acid, they neutralize to form a salt. The “salt” is actually soap and glycerin.

Triglycerides (oils/fats) + alkali (lye) = soap + glycerin (a natural emollient that occurs during the soap making process.)

As you know, fats or oils don’t mix well with water. Lye is the key ingredient that allows two non-compatible substances (oils and water) to come together to form a new substance—soap.

While it may seem counterintuitive to add sodium hydroxide (a known irritant) to a product you rub all over your skin, when the soap has undergone saponification, there’s no lye left in the finished soap—it has neutralized.

Most standard soap recipes use around 5 percent superfat (extra fat/oil to ensure all sodium hydroxide is neutralized).

While sodium hydroxide lye has a pH of around 13.5, a finished bar of soap generally has a pH between 8 and 10. (If you recall, a pH of 7 is neutral.)

In a nutshell, here’s a high-level overview of the cold process method:

- Make your lye solution by carefully adding lye to water. Allow to cool.

- Measure oils and fats. Melt together and let cool.

- Once both the lye mixture and the oil/fats mixture are roughly 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees Celsius), or within several degrees of each other, add lye mixture into oils. Blend until trace.

- Add essential oils, and other add-ins as desired.

- Pour into soap molds and allow to harden.

- Unmold and cut into bars.

- Allow to cure for 4–6 weeks.

Is homemade soap using lye still considered natural?

Yes, there’s simply no way to make good bar soap from scratch without using lye. If you use natural ingredients in your soap recipe such as nourishing oils, goat’s milk, or honey, this is still considered natural even if you use commercially produced lye.

While there’s no standard definition of what makes up a bar of “natural” soap, I think we can all agree that soap made without the use of chemical additives would be a good starting point.

Compare this to many commercial soaps which contain sulphates, such as sodium lauryl sulphate (SLS) and sodium laureth sulphate (SLES). Most mass-produced soaps also contain synthetic fragrances, which contain a plethora of chemicals and compounds.

You might like

Sodium Hydroxide – Pure – Food Grade (Caustic Soda, Lye), 2 Pound Jar

- Top quality, premium lye that’s great for making soap, as a cleaner, or for food prep.

- Food-Grade USP/FCC.

- Reclosable HDPE jar.

Found on Amazon

Check Current Price

Those in Canada and the UK should be taken to the product listing in your region.

Why isn’t lye or sodium hydroxide listed as in ingredient in soap?

Depending on the labelling laws in your area, some homemade soaps aren’t required to list sodium hydroxide as an ingredient because there simply isn’t any lye present in the finished soap. (Besides, most producers know that the word “lye” is enough to scare many people away from using the product.)

Many soap makers simply list the oils, butters, waxes, and other additives used.

Or, sometimes you’ll see weird names such as sodium tallowate (lye + tallow), or sodium palm kernelate (lye + palm kernel flakes). These are the scientific names of certain fats that are saponified with lye.

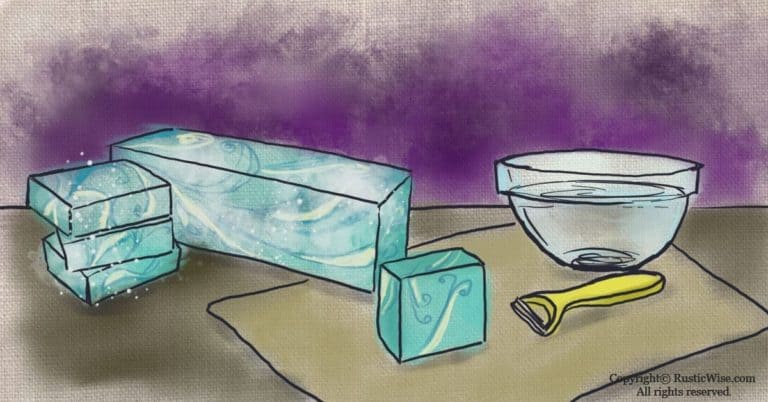

Don’t want to handle lye? Make melt and pour soap

The good news for those of you who are wary of handling lye is that there’s a lye-free soap making process. It’s the melt and pour method of soap making.

You can buy a variety of melt and pour soap bases such as glycerin, goat’s milk, and coconut milk, to name just a few. The great thing is you just need to cut your soap blocks into cubes and melt them! Add any additives you like, then pour into soap molds.

The melt and pour soap bases are already fully saponified so you don’t need to handle lye. Melt and pour is a great way to get your feet wet in the world of soap making. It’s also a wonderful way for kids to safely make their own soap.

The takeaway

While you can make your own natural lye by leaching hardwood ashes with water (to produce potassium hydroxide) most soap makers choose to instead buy a bottle of sodium hydroxide lye. Sodium hydroxide produces a harder bar of soap, and when used safely and by following a good soap recipe, the harmful properties of lye are neutralized in the finished soap. So, yes, lye is perfectly safe to use for making homemade soap!

Related questions

What is a natural replacement for lye?

Lye is an indispensable ingredient in soap making, and there simply isn’t a good replacement for it (if you want to make soap from scratch). If you want to make soap without handling lye, you can buy premade soap bases and make melt and pour soap.

Commercial lye is made from a solution of salt and water that undergoes electrolysis to form two separate products: sodium hydroxide lye and chlorine.

You can try making your own natural lye of hardwood ashes, but this is time consuming. Most people who make true soaps buy a bottle of sodium hydroxide flakes to use.

I’ve heard of some people using baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) as a replacement for lye to make soaps. I’ve never done this myself, but I’ve heard you can still make bar soaps as baking soda is an alkali (albeit a weaker one than lye). The results of baking soda soap (without any lye) are lackluster—they’re softer, and don’t lather as well. My question is, why wouldn’t you just use sodium hydroxide lye to make a better bar of soap?

New to making soap? 🧼❓

👉We have a fantastic overview on the whole soapmaking process here: read our Timeless Guide To Soapmaking.

If you would like to see our soapmaking posts organized by topic type, see our Soapmaking Collection.

Would you like more timeless tips via email?

Fun tips to help you live an independent, self-sustaining lifestyle. Opt-out at any time.

References

- ChemicalSafetyFacts.org, Sodium hydroxide, https://www.chemicalsafetyfacts.org/sodium-hydroxide/. Accessed November 2021.

- Statista, Caustic soda production in the United States from 1990 to 2019, https://www.statista.com/statistics/974228/us-caustic-soda-production-volume/. Accessed November 2021.

- BBC, Electrolysis, https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zpxn82p/revision/1. Accessed November 2021.

- EuroChlor, Membrane Cell Process, https://www.eurochlor.org/about-chlor-alkali/how-are-chlorine-and-caustic-soda-made/membrane-cell-process/. Accessed November 2023.

Author: Theresa Tesolin

Theresa is co-founder of RusticWise. She helps people unleash their inner DIY spirit by encouraging them to get dirty and make or grow something from scratch.